General Laborer

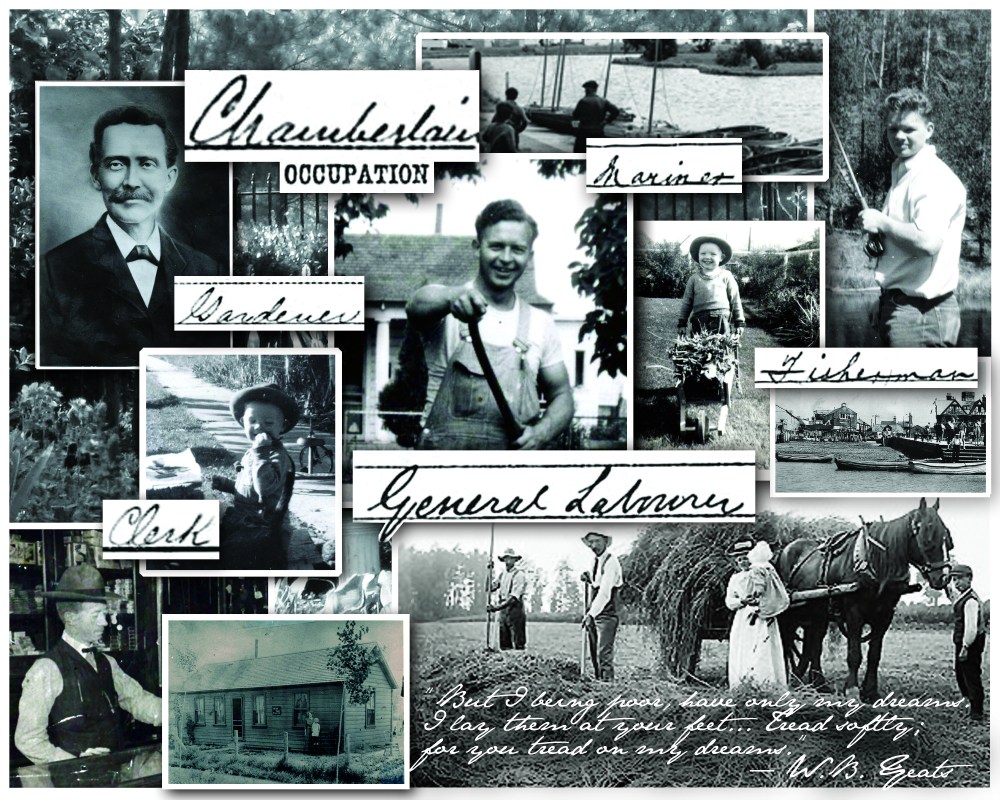

I have looked at enough census records to know that the center column—the occupation—is where much of the lives of my ancestors are revealed. While many researchers take pride in a discovery of distinction—a gentleman perhaps, or a minister, doctor, or politician—I have yet to strike gold in a vein of worldly merit. Rather, as I have turned back to my fathers and mothers, I have found them laboring in the trades of the lower class as fisherman, farm laborers, gardeners, maids, and most frequently, general laborers. It is this last title of general laborer that has caused me to reflect on the merits given to the poor, unskilled, and weary. I picture the enumerator, peering up from his broad census sheet, quill poised. Occupation? Laborer.

What more do we know of some of our laborers? My fifth great grandfather, a farm laborer in Essex, died of “sloughing of the foot”, leaving behind ten children. My husband’s family worked in the damp fields of Northern England. Such laborers did not receive payment for their work until after their term of hire was completed. Poor and hungry, they ate raw turnips in the fields to stave their hunger.

What more do we know of some of our laborers? My fifth great grandfather, a farm laborer in Essex, died of “sloughing of the foot”, leaving behind ten children. My husband’s family worked in the damp fields of Northern England. Such laborers did not receive payment for their work until after their term of hire was completed. Poor and hungry, they ate raw turnips in the fields to stave their hunger.

Our laborers were not always virtuous. My third great aunt Ellen Chamberlain was brought to trial for stealing two loaves of bread. Trial notes reveal when confronted, “she then took the loaf from under her shawl and said “This is the loaf—pray, sir, forgive me.” For this she was given two months hard labor, a sentence of apparent leniency. My fifth great grandfather Ben Chamberlain was relieved from his apprenticeship in 1785 due to “disorderly behaviour and frequent absences”. Rumors abounded of drinking and ill tempers, an apparent occupational hazard of our ship laborers.

Then there were the deaths, inexplicable and beyond comprehension. My sixth great uncle was a farm laborer and father of eleven children; all of his children died in childhood save two. When my third great aunt was pregnant with their first child, her husband Edward Austin worked as a laborer in a neighboring town. While he was digging a ditch when a man nearby leaned his rifle against a tree. The rifle fell and fired accidentally, mortally wounding the young father-to-be. Most of our fathers were taken young. Looking back six generations down to my grandfather, all passed in their 30’s or 40’s with the exception of two.

And the women? What is not written can only be imagined. They suffered ill-timed relationships and abandonment, and worked as maids, nurses, and farm laborers at tender ages. Many did not rest in their old age, working as cleaning women or doing laundry.

When our Chamberlain family reached New York City in 1888, there could not have been a more obscure family with more dubious health and almost no wealth. When they arrived in Salt Lake City a few weeks later, they were taken to the Tithing Yard for needed food and supplies. It was there on a bale of hay that their infant son Robert died, a pained and mournful offering in the midst of others sacrifice. A few months later, his mother Ellen Gardner Chamberlain died from tuberculosis.

Their grandson—my grandfather—was also laborer. His forearms—as wide as melons and too large for sleeves—have found a place in me. He taught his son—my father—how to build, paint, and care for a home and yard. Once my mother famously waited for my dad for a date while he finished the lawn: mow twice, once in each direction, then rake and bag the grass.

Their grandson—my grandfather—was also laborer. His forearms—as wide as melons and too large for sleeves—have found a place in me. He taught his son—my father—how to build, paint, and care for a home and yard. Once my mother famously waited for my dad for a date while he finished the lawn: mow twice, once in each direction, then rake and bag the grass.

My own body and soul bears the traces of the laborer. My legs, large and strong as rocks, have carried my children up mountains and pushed me down miles of roads. I have strong hands arms like my fathers before me, that can open jars and till gardens. I have inherited a willingness to work—to jump, climb, shovel and lift. While my stomach has never soured from raw turnips, or my coat hidden bread, my blood carries the virtues and flaws of the laborer. My face reveals the crease of worry, my clothes show stains of earthly chores, my skin maps the scars of adventure and my soul the ache of every weakness.

When I die, don’t list my jobs; just write General Laborer under my name—this title I tenderly share with those laborers who have gone before me. To achieve such a distinction as this would be to have prepared myself in all things, to have worn out my body and mind completely, to have worked as they worked, so as to meet them on level ground.

When I die, don’t list my jobs; just write General Laborer under my name—this title I tenderly share with those laborers who have gone before me. To achieve such a distinction as this would be to have prepared myself in all things, to have worn out my body and mind completely, to have worked as they worked, so as to meet them on level ground.